Download: 006_John_Bunker_Rowan_Jacobsen.mp3 [25.6MB, 28:01]

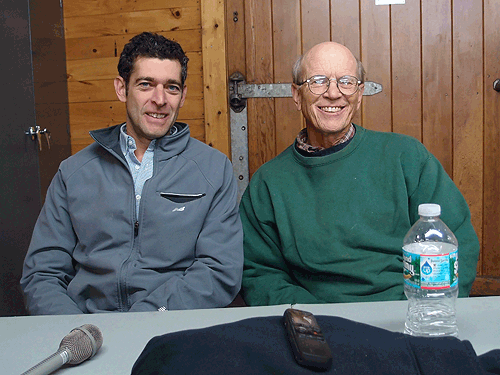

ERIC WEST (Intro): In this interview, I am on location at Franklin County CiderDays in Massachusetts. I had the great fortune of talking with both John Bunker and Rowan Jacobsen after their talk on Saturday morning.

John Bunker, he’s an apple expert—one of the US’s most pre-eminent apple experts. He’s based out of Palermo, Maine. There he runs his own heritage apple CSA program called Out on a Limb. He is the founder of Fedco Trees, where you can order many different heirloom and cider variety apple trees. He is the driving force behind the Maine Heritage Orchard, where varieties that are indigenous to Maine are being planted, with the hopes of preserving them for future generations. And he’s also the author of Not Far from the Tree, which is a look at the apple and cider culture of Palermo, Maine—and I guess, by extension, of New England and the country as a whole.

And Rowan Jacobsen, he’s the James Beard Award-winning author of A Geography of Oysters and many other great articles and books. I first came across his work in American Terroir. But his most recent book is on apples, it’s called Apples of Uncommon Character. And he’s a very talented writer—food writer, travel writer, talking about the sustainability of our food systems.

So without further ado, this is our talk at CiderDays from November 1st, 2014.

ERIC WEST: It’s November 1st. We are at Franklin County CiderDays. And I’m very privileged to have two amazing, amazing authorities with me here.

On my right is John Bunker. You may know him as the founder of Fedco Trees. He is the author of Not Far from the Tree. And on my left is Rowan Jacobsen, also a very talented authority. His latest book is Apples of Uncommon Character.

Guys, thanks for being here with me today.

ROWAN JACOBSEN: Thank you.

JOHN BUNKER: Thank you.

WEST: So John, I’m going to start with you. You guys just did a talk on fruit exploration. And that is something that seems to be very near and dear to your heart. Can you talk us through a little bit about the history of apples in Maine, and why it’s necessary now to go explore for some of that fruit that was once grown in Maine?

BUNKER: Well, it’s a long history. It would have begun before 1600 when fishermen from Europe were fishing off the coast of Maine. Every ship had the apple barrel. So the apple cores, the apple seeds were deposited into the ocean, all over the islands. So off the coast of Maine you find there were orchards very early on, from seed. Planted—either on purpose or inadvertently—by the fishermen from Europe, largely from Portugal. Nobody knows a lot of the details except that we know that there were orchards very early on.

Then when Europeans began to settle on the coast of Maine and then inland, everybody pretty much lived on some version of a farm. Every farm had an orchard. The orchards were almost exclusively from seed. And because of the biology of an apple tree, every seed is unique. So really what was happening was this great inadvertent breeding experiment where every farmer was an apple breeder, selecting the best of their seedlings, occasionally naming them, and then passing them around from scionwood, from grafting. Because the only way to replicate them is from grafting. So that by the middle of the 19th century, from Maine to Georgia and out to the Mississippi River, there would have been tens of millions of apple seedlings, and many many thousands of named American varieties.

WEST: I believe you mention in your book that at one point in Maine’s history that apples were probably the best land use, in terms of making a profit? Is that correct?

BUNKER: Yes, absolutely. One of the convenient things about apples is that you could use your marginal land for your apple orchards. Your best farmland would be used for your row crops. Then probably your next best land would be used for your pasturing. And then your rockier land that you would not be able to, or didn’t want to pull the rocks out—and you definitely didn’t want to try and plow it—you could put your orchards in there.

WEST: Can you talk a little bit about the transition from seedling fruit to grafting…the New England Seven, a brief history of that? Because something that I noticed in the book is you felt that the farmers had this self-sufficient lifestyle and they almost had to give that up in a way once they started grafting varieties. Can you talk a little bit about that?

BUNKER: There was a period when the farming model was one of a small, diversified, mostly self-sufficient farm and community. And in that model you don’t need uniformity and named varieties. Those kinds of more modern agricultural elements are way less important. Because what you’re doing is you’re providing for yourself—what you call things, and to some degree the quality…the quality just needs to be good enough for you. And that could be an animal, the breeds or not-breeds of animals that were used. And the seed that was used for the crops. Because people were not selling products, it was a whole different mindset of how you look at what you produce.

The state survives on taxes. It’s very difficult to tax people who are living in a subsistence, self-sufficient economic model. Because they don’t need anything from the state. There were not roads, and so forth. So as the roads began to improve…in ways that I don’t totally understand, it has to do with the Temperance movement. Some people feel like the transition from the more self-sufficient model to the more retail model—the farm as an economic entity—how much does that have to do with Temperance? Because the seedling orchards were ideal for creating cider. And cider was the perfect drink for the farmers, because they could produce it for nothing on their own farms.

Some people think that the Temperance movement was about trying to clean up people’s behavior because they were drinking too much. But I also wonder if the Temperance movement was about the state gaining control over the farm as a way of generating income through taxation. Because as I said, if you’re producing everything on your own farm for your own use, how can you tax that? But starting around 1830 or so, and then progressing throughout the 19th century, there was this movement—whatever the reason was—away from the seedling, self-sufficient farm model to the grafted tree.

Also, as you sell more of a product, there is the necessity for your customer to be able to recognize what it is that you’re selling, especially if you’re not selling it on your farm. What we could have done, is we could have had a model where in this valley, these apples were grown. In that valley, those apples were grown. And so forth. Similar to the way different wines in Europe or cheeses or whatever [are marketed].

But instead, we slowly moved ourselves toward the commodity version of—in this case orcharding—where instead of having millions of seedlings, we then went to thousands of named varieties, a few of which were recognizable over a large geographical area. And then from there, to a reduced number of recognizable varieties, down to seven in 1927 or so. And then down to only a small handful after 1934 and the big freeze in 1934.

WEST: So Rowan, where your book picks up is where we do have the grafted varieties—the named varieties. How did you go about selecting the varieties for your book? Was there a sense of trying to find things that you enjoyed and wanted to repopularize? What was the thought process in picking the apples that are in the book?

JACOBSEN: I wanted to give people a tool to learn more about whatever apples they were coming across. So I tried to make sure that the main apples they were coming across were in there. But I also wanted to take that conversation to the next level. I also really wanted to include apples that they were unlikely to come across—apples that had a really good reason that it would be worth seeking out. Either because they were incredibly delicious, or had a particularly interesting story to tell that helps tell the overall story of the apple.

Or sometimes, there are a few in there that are purely in there just because it’s an awesome picture! They might not even taste that great, but they also helped to…I’m basically trying to get that moment where people, their mind clicks open and they start thinking about the apple in a different way.

WEST: I know that apple books are very popular. Was it very intimidating to jump into a topic like this that a lot of people have done? And worried about—I guess you reached out to John and probably to people like Tom Burford—was this an intimidating topic because so many people have covered it? The idea of apples being as American as a fruit can get…was that a challenge for you?

JACOBSEN: No, it wasn’t intimidating. One of the reasons I wanted to do the book was because I saw that there was this gap to be filled. There are apple books out there that were guides to varieties. But they were really, mostly written by pros for the maybe the backyard gardener. And I felt like there wasn’t anything out there that was speaking to the Whole Foods shopper who might not ever grow a tree in her life, but had an interest in food. And with this book, she might then start to develop a whole different relationship with apples.

So that hadn’t been done, that was wide open. I was coming at it from the consumer end, and didn’t necessarily need to be an expert in the same way. The famous dictum about writing—Write What You Know—more and more, I think that’s true of fiction. It’s really important with fiction that you write what you know because you have to convince people of the authenticity of what you’re writing about. But with nonfiction I think it should be Write What You Don’t Know. Because when you’re new to a subject, it’s magical to you. You’re fascinated by it in the same way that the casual reader is going to be fascinated by it. Sometimes when you’re too close to a subject, you forget what was interesting about it to outsiders in the first place.

With oysters—my first book was about oysters—and at that time, I was writing about what I didn’t know. And since then, I’ve come to know everything about oysters so well. Because it goes on and on—I know the growers, I know the whole industry part of it—I think I probably don’t write as well about oysters now. I forget, I get into some minor trivial things that seem huge to me, but the outside reader could care less about. And I forget the big picture.

WEST: I guess that’s why we call them enthusiasts, right? Because you have to be enthusiastic about something. Once you progress to being an expert, you lose some of that enthusiasm perhaps.

JACOBSEN: Sometimes you just don’t see the forest for the trees. You’ve made it to the center of the trees.

BUNKER: Maybe that’s who your best critic is, too. Because I know when I write, the person that I want to read it first, to tell me about it before it goes out somewhere, is the person that doesn’t know much about it.

JACOBSEN: Exactly. Yeah, it’s the same thing.

BUNKER: Because then they can look at it and say, this does not make sense!

WEST: You need to be able to describe something to your grandmother. If you have a business idea, you need to be able to describe it to somebody who clearly does not keep up with trends.

Let me ask you guys this. I’ll throw it out to both of you. Are you surprised that hard cider is one of the catalysts for generating interest in these uncommon varieties? John, had you ever thought that would be something that would get people interested in what you’re doing? That hard cider would ever experience a renaissance like it has?

BUNKER: When I was rather young, I pressed a lot of cider. And while I was pressing cider and selling some—selling barrels to my friends and so forth—I found myself thinking about agriculture in general, and orcharding. And how could we create a way of using apples that would be profitable for the orchardist. Because twenty or thirty years ago, the orchardists, like many other farmers, were basically just a dying breed.

One commercial orchardist told me that they were selling their juice apples to one of these big juice companies for three cents a pound or something. Whatever it was, it was just disgraceful. It was costing more money to produce the apples and not even pick them, than it would be to sell them.

I spent a lot of time out by myself in old orchards, old trees and so forth, and I’d always be musing about these things. And the one thing that I always came back to was alcohol. That that was one way I thought that some day there could be a revival of the whole apple industry. But I struggled with it, because of all the stuff about alcohol! Should you drink alcohol, blah blah blah.

So then—maybe 15 years ago—I started to hear about Steve Wood [of Poverty Lane Orchards & Farnum Hill Ciders]. So I went and visited him, talked a lot about cider. And he was the one who really introduced me to the British and French cider apples. I started to get scionwood from him, started to graft trees. And still I thought, this is interesting, it’s fun, and it is part of a really, really small scale—almost amateur—way of using apples. And then all of a sudden—it crept along at a snail’s pace—and then it reached that hundredth monkey or whatever, and it just took off!

I guess I’m not totally surprised. I’m more delighted than surprised. I was at CiderCon in Chicago last February, and there was this salon type of thing—after CiderCon, the next day, on Navy Pier, there was this gigantic room on Navy Pier. And it was packed with people. You were a foot away from the person nearest you, and the entire thing was cider, cidermakers all around the perimeter. And Steve Wood was there. It was just this chaos of people drinking and talking.

And so I went up to Steve, and I said, “Ten years ago, would you have ever believed that this would have happened?” Because he was just out in the dark. And he said, “Two years ago, I wouldn’t have believed this was ever going to happen!”

It’s probably similar to what happened to beer, except that it already happened to beer. With that transition from Budweiser to craft beer. And now that it’s happened once, this version of it is going to happen a lot more quickly. Because people get it that the apple juice version of hard cider is an interesting thing, but it’s going to be a lot more fun to make it more sophisticated. So it’s just rolling now at this point.

In Maine, I would say probably every month there is a new commercial cidermaker in Maine. With an actual license and products to sell and so forth. It’s just unbelieveable.

WEST: That’s excellent. Let’s close with this. Rowan, I’ll throw this to you first. What does cider have to do in order to stay in the public consciousness and continue growing the way that it is? What obstacles does cider have to overcome in order to reach widespread acceptance in the US?

JACOBSEN: I do think it has some obstacles. I’m also shocked that it is becoming as mainstream as quickly as it is. I started making my own cider like 10 or 11 years ago. And I fermented it out dry, very classic farmhouse cider. Four out of five people—I loved it, I thought it was fascinating—but four out of five people who tasted it, did not love it.

A dry cider is still a weird drink to most people. Somehow the industry…like John was saying, Steve Wood, his cider is off-putting to a lot of people who have never had anything like that. It’s clearly not what…people think it’s going to be white wine, or something sweet when they taste it. And it’s not either one of those things. It is its own entity, which is great, that’s partly why I love it so much.

What’s it going to be as we go forward? I don’t think anyone knows. It’s interesting. This [Franklin County CiderDays] is the redoubt for dry ciders. You go out to the Pacific Northwest, to their cider fests, and it’s a completely different drink and a completely different atmosphere.

So it’s going to be really interesting to see—and I know internally, the industry is really wrestling with this. Because some ciders are more like the wine coolers of 2014. A sweet, very simple drink. Some are bone dry. And some are like the craziest craft beers. There are these guava ciders out there! Every flavored cider you can think of is now being made—artisanally—by somebody in Portland, Oregon or somewhere like that.

There’s so little definition of what cider is. And that’s going to be…maybe a problem down the line to a certain extent. Or maybe it’s all going to shake out, and there will be several different branches of the tree that cider follows, and each branch has its own following.

WEST: And some of it may hinge upon the success of these varieties getting planted again. John, is that something that’s maybe holding the industry back right now? That there isn’t widespread access to some of the apples that cidermakers would like to use to make cider with?

BUNKER: Yes. The lack of of sufficient quantities of more complex flavored varieties is a big issue right now. Some orchardists are planting thousands of cider varieties. Because the Macs and Cortlands and Golden Delicious and those sort of apples, they’re very good apples to practice on as you’re learning how to make cider. But because there’s no hops—or rarely hops are used in cider, or other additives—it’s all about the apples. For those that want to…really, no matter what you want do to with your cider, it’s going to largely be about the varieties.

It’s the difference between having one of those little watercolor packs that has six colors in it, and then becoming a more sophisticated artist where you need like a hundred different tubes of color. So right now, people are trying to—as rapidly as possible—plant the European cider varieties that have more tannins and so forth. And go through existing American varieties and try to find ones that would be good in cider. And discover new seedlings that are out there in the landscape. Because many of them have a lot of flavors that will come through the fermenting process.

So in a way, it’s a renaissance of apple orcharding that is accompanying the cidermaking. Which I think will be really exciting.

JACOBSEN: And what a wonderfully unlikely problem to have, that you can’t get enough Dabinett!

BUNKER: Right! You can’t get enough weird [apples] that you can’t even eat fresh, and people just want it!

JACOBSEN: To see these hipsters with their Kickstarter campaigns so they can create these cider orchards, this thing that no one’s thought of in 150 years. I don’t know. It’s like Tony Bennett. It was out of fashion for so long that it got rediscovered by the kids.

WEST: Well it’s an exciting time for apples, and it’s an exciting time for cider. Thank you guys for joining me today. Rowan Jacobsen, John Bunker, thank you very much.

BUNKER: Thank you very much.

JACOBSEN: Thanks, Eric.

WEST (Outro): It was a great pleasure for me to sit down with John and Rowan, and I hope you enjoyed that interview.

I would highly suggest reading both of these guys’ work. A good place to start might be the piece that Rowan did on John in Mother Jones magazine back in 2013. The title is Why Your Supermarket Sells Only 5 Kinds of Apples. I think it’s a great one. Even if you’ve read it, go back and re-read it, I think it’s fantastic.